Fort Walker/Welles

In May 1861, General P. G. T. Beauregard recommended the construction of this earthwork fort on Coggins Point Plantation to guard the entrance to Port Royal Sound. The fort was named in honor of Confederate Secretary of War, L.P. Walker. Colonel William C. Hayward, Eleventh Regiment, South Carolina Volunteers, was in command of the fort, and General Thomas F. Drayton was in charge of the overall defenses of Port Royal Sound. On November 7, 1861 the most formidable expeditionary fleet to date captured Fort Walker for the Union.

On November 8, 1861 Brigadier General Thomas West Sherman issued General Order #28, changing the name from Fort Walker to Fort Welles in honor of Gideon Welles, United States Secretary of War.

South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology (SCIAA) original listing,

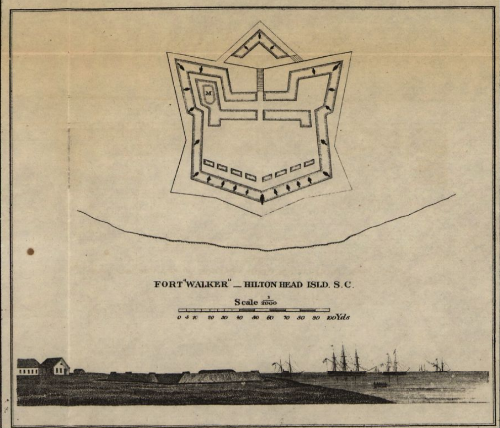

U.S. Coast Survey 1862, A.D. Bache (Library of Congress) – View Image

The battery built near the bluff was christened Fort Walker. No doubt the name was in honor of the Confederate Secretary of War, L.P. Walker, with the hope that the Secretary would somehow find the heavy artillery needed… Perhaps there was also some idea of honoring W.S. Walker, then in charge of the Third Military District, of which Hilton Head was a part.

Work began in July, with the island planters furnishing the slave labor for hauling palmetto logs, digging trenches, erecting a powder magazine, constructing gun emplacements. The slaves sang as they worked . . . But as they sang they slurred the words whenever a white man was near . . . told of the coming freedom . . .

No more peck of corn for me, no more, no more

No more peck of corn for me

Many thousands go

No more pint of salt for me, etc.

No more drivers lash, etc.

No more mistress’ call, etc.

The song would spread throughout the southland . . . [experts] believe it was first sung on Hilton Head in that dark summer of 1861 while slaves labored at Forts Walker and Beauregard. (Holmgren 81)

Major Francis D. Lee was in charge of planning and constructing the defenses. The author describes the guns received, few of which met the requirements of the fortifications either in caliber or number. Work was planned for Braddock’s Point, Seabrook Landing on Skull Creek, and infantry earthworks to the south of Fort Walker. Most of this work was barely started on November 7th. “October 17 . . . were 362 men to defend Fort Walker . . . reinforcements . . . new total of 622.”

Brigadier General Thomas Fenwick Drayton headquartered both at the Pope house on Coggins Point and his own home, Fish Haul. “If anyone knew how to defend the island, he would. Thomas Drayton knew every road, every woodland trail; knew where the offshore waters were deep enough for landing. But without the necessary guns . . . “

In immediate charge of the fort was Colonel John A. Wegener and 220 men of the First Artillery, South Carolina Militia. Major A.M. Huger was in charge of the firing. Captain Josiah Bedon and Company C of the 9th (later the 11th) South Carolina Volunteers manned the waterfront. Captains Werner and Harmes with A and B Companies of the German Artillery, and Captains Canaday and White of the Infantry brought the total manpower to 687, later to be increased to about 1,450 . . . Acting as Drayton’s aides were young lieutenant J.E. Drayton, captains T.R.S. Elliott, Ephraim Baynard and Paul Seabrook, all of island families. [When Drayton returned to Beaufort he left Colonel William C. Heyward in command. He requested reinforcements from Coosawatchie and Charleston] . . . But even if more troops came before Federal attack, Drayton must have known the island had no chance. [Carse also places Lieutenant William Drayton, son of the general, at Fort Walker.] (Holmgren 82-83)

[November 7, 1861] Then, from Fort Walker, a gun slammed and a round of shot hit the water near the head of the Federal column. It was 9:26 on this cloudless morning, and one of the most important battles of the war had begun. (Carse, Robert, Hilton Head In the Civil War; Department of the South 12)

This section of the book presents a vivid description of the battle and the Federal landings with many quotes from The Harper’s Weekly reporter and the correspondent from The New York Herald on board transport ships. They, along with The Harper’s Weekly artist are not named. (Holmgren 89-97)

Quoting from a talk given by Vice Admiral Edwin B. Hooper to the Hilton Head Historical Society.

” . . . shortly after 2 pm, the Confederate defenders decided to evacuate Fort Walker. Commander John Rodgers, sent ashore with a flag of truce, hoisted the Union colors. Then at 2:45 Commander C.R.P. Rodgers landed with marines and a party of seamen . . . General Drayton was subject to heavy criticism for abandoning the area . . . he had no sensible alternative. His 1,000 men, including the 622 on Hilton Head, were green, untested, and outnumbered 12 to 1. Never had a fortification received such a high volume of fire power over a comparable period . . . ammunition was nearing completion and all but three of his guns on the water side were disabled or dismounted. [The Union forces] . . . relied heavily on naval mobile support such as would be used in World War II and the Vietnam War.” (The Island Packet, April 19, 1973)

“At 2:45, as flagship, the Wabash made the signal to cease firing.” (Carse 19)

“The Union forces had lost eight dead and twenty-three wounded, and the Confederates in their defense had given fifty-nine killed or wounded. [. . .] by actual count 12,653 [Federal troops] had landed on Hilton Head.” (Carse 22)

“The Confederates were really ‘done in’ by two gunboats to the north of Fish Haul Creek and another . . . on the edge of the shoals to the south . . . no guns were in place on either flank of Fort Walker.” (Carse 17)

Commander Percival Drayton, brother of Confederate General Drayton, was in command of the Federal warship Pocahontas that attacked the southern flank of the fort. (Carse 16)

The name of Fort Walker he [General Sherman] changed to honor Gideon Welles, United States Secretary of the Navy. A few days later, November 22, 1861, he ordered that the post office and townsite on Hilton Head near the fort be named Port Royal . . . remained the official designation for the town of Hilton Head . . . ’til January 1872, when Hilton Head was restored as the title. (Holmgren 96)

Reverend Thomas Heyward, one of the missionary teachers, returned to the island in 1888. The long pier at ‘Port Royal’ was gone, washed away and never replaced. “Not only was Fort Walker abandoned, but a good share of the parade grounds and part of the old general hospital had been washed away.” (Holmgren 117)

Throughout all these years of peace the Federal government had still kept possession of 803 acres at Coggins Point where Fort Walker was located. During the war days of 1898 when there was once again threat of Spanish invasion, the fort was reactivated and a new type of dynamite [cynamite] gun installed [actually 1902] . . . The war ended and the buildings were turned over to the quartermaster’s department, empty and abandoned, on August 17, 1899. The land remained government property and the Pope family had no chance of reclaiming it. (Holmgren 119)

When the United States joined the Allies in 1917, the abandoned barracks at Coggins Point were cleaned and repaired and the big guns were fitted to their emplacements. Troops came but did not stay long, although they kept lookout for enemy submarine attack right up until Armistice Day. Then the soldiers left again. . . (Holmgren 120)

[Landon K. Thorne and Alfred L. Loomis] These two Northerners even acquired the last piece of the confiscated property taken by the Federal government at the fall of Fort Walker in 1861. This last plot, the 803 acres of Coggins Point, had been declared a military reservation in 1874 and was finally offered for sale by the Secretary of War in 1927 at the price of $12,600 . . . (Holmgren 123)

See Port Royal section of this book for a detailed description of Fort Walker.

Ammem, Daniel, Campaigns of the Civil War (CW10), The Atlantic Coast, p. 30

Following the May 1861 recommendations of General P. G. T. Beauregard, Captain Francis D. Lee of the Confederate States Engineer Corps began construction of fortifications on Hilton Head in July, chiefly a battery located on Coggins Point Plantation near the entrance to Port Royal Sound. It was christened Fort Walker in honor of Confederate Secretary of War, L. P. Walker. Slave labor was used for cutting, hauling and placing palmetto logs, digging trenches, constructing gun emplacements and a powder magazine. Unfortunately, almost no heavy caliber armament could be secured to furnish it. Col. William C. Heyward, Eleventh Regiment of South Carolina Volunteers, was in command with Gen. Thomas F. Drayton in charge of the overall defense of Port Royal Sound. When the most formidable expeditionary fleet ever assembled up to that time arrived to attack Hilton Head, the 24 guns of Fort Walker were quickly put out of commission and Gen. Drayton ordered its evacuation November 7, 1861.(Peeples, An Index to Hilton Head Island Names (Before the Contemporary Development) 17)

Fort San Felipe

Fort Walker/Welles

Fort Howell

Fort San Salvador

Fort Mitchel

Fort Sherman

Fort San Marcos

Charlesfort

Join The Library

As a Member, you will have full access to the library facilities, publications, classes and our online resources as well as the talents and expertise of our volunteers who will help with your research project.